[mythopoesis: the making of myths, or fantasy]

Down the ages, some of the most heart-felt poetry written deals with the creative process, particularly the loss of inspiration. Yet, anyone who has written a well told tale, or painted an especially effective picture, is conscious of the labor involved in successfully completing the work. These two aspects of the creative process – inspiration and labor – seem especially contradictory when one attempts to describe mythopoesis. On one hand, any attempt to write the history of a fantasy world backwards from a particular story cannot be done without generating conflicts or a degree of shallowness. Yet on the other hand, backwards is the only way the “history” appears to the writer.

Down the ages, some of the most heart-felt poetry written deals with the creative process, particularly the loss of inspiration. Yet, anyone who has written a well told tale, or painted an especially effective picture, is conscious of the labor involved in successfully completing the work. These two aspects of the creative process – inspiration and labor – seem especially contradictory when one attempts to describe mythopoesis. On one hand, any attempt to write the history of a fantasy world backwards from a particular story cannot be done without generating conflicts or a degree of shallowness. Yet on the other hand, backwards is the only way the “history” appears to the writer.

Many a writer has labored under the assumption that these two forces are the only ones working in the creative process. Dorothy L. Sayers in The Mind of the Maker (Greenwood Press, 1970) makes a powerful argument for calling the process trinitarian. In her book, she uses the metaphor of the human maker to study the Holy Trinity, and then points out that the comparison works in the other direction as well.

She then proceeds to offer the following equation:

The Father = idea

The Son = energy / activity

The Spirit = power

For a greater personal clarity (but no violence to Sayer’s main arguments), I offer the following substitutions:

The Father = idea = P-function (pater)

The Son = form/technique = F-function (filius)

The Spirit = communication / energy = S-function (spiritus)

With these terms it becomes much easier to describe the creative process, and explain the actual experience of “inspiration versus labor”.

The P-function, that is, the story ideas that a writer gathers, operates “outside time”. What this means is that a Sub-Creator will enter his fantasy world through a particular story he wishes to tell, and then acquire the “history” of this fantasy world in a seemingly chaotic fashion. He may find that the first story he wanted to tell occurs in the middle of his world’s history, that the next story occurs at the world’s beginning, the third at the end, the fourth just before the original tale, and so on. “Inspiration” or idea-gathering is not a tidy process. It is not a formal process.

The F-function is a formal process. This aspect of the creative trinity involves the “physical” nature of the ideas gathered in the P-function. It involves both the choice of format for containing the idea (Will it be poetry or prose? Drawing or sculpture?) and the technique of the artist. The F-function of the creative process is perhaps the easiest of the three to teach aspiring writers. To this function belongs the activity, the practice, of learning composition – in any of the arts. Sir Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses to the Royal Academy emphasizes that the practice, study, and knowledge of one’s art is a matter of labor, and that without that labor, that form and technique, ideas would be shapeless. Concisely, he states in the Second Discourse, “excellence is never granted to man but as the reward of labor.” Mastery of technique will give ideas their best incarnation. To quote from the Second Discourse again:

If you have great talents industry will improve them; if you have but moderate abilities industry will supply their deficiency. Nothing is denied to well-directed labor; nothing is to be obtained without it.

The third corner of the creative trinity is supplied by the S-function, the energy or communication of the work, or as Sayers calls it, its Power. It is what the artist puts into it and what the audience gets out of it. It is that which is communicated. It is in the S-function of mythopoesis that the Sub-Creator’s love for his creation makes its presence known. Without the S-function, a creation is only going to be two-dimensional, form and idea, and it will fail to communicate.

An awareness of these three functions of the creative process allows one to understand the many moods of creativity. Indeed, it allows not simply understanding but the ability to describe the moods. There will be times when the artist has what he knows to be a good idea and also the most suitable form for that idea, but he has – at that moment – no feeling for it, no urge to communicate. Or he may have acquired mastery of techniques and form, be filled with a desire to communicate, and yet be directionless, without a solid idea. Or he may be possessed of an idea and the burning desire to communicate it, and yet be at a loss, lacking the “correct” form. In each case, the artist who trusts his sense of what “fits” is likely to wait until the missing third presents itself, while the artist who “just wants to get it done” will impose the third component and let it go at that.

On the rare occasions when all three functions are working evenly, in unison, the artist will experience the wonderful elation poets speak of, be it called “inspiration,” “the Muse,” or “magic.” When the creative trinity is singing in a three-part harmony, the artist will feel that never has his work been so easy, for the ideas will be coming smoothly. Yet also never will he have worked so hard, searching for the right word or angle, taking care that the right choice will be made even in the smallest detail. And through it all will run a joy and delight in the whole process, the ease and the labor. But any novice should be warned: this is the rare experience. It is not the everyday experience. It comes unexpectedly, and it cannot be pursued. It can be prepared for, by gaining mastery of technique, but one cannot command it to appear. This, say some poets, is what it is like to be God, and they are not far wrong. But let Sir Joshua have the final warning voice about “inspiration.”

Such is the warmth with which both the ancients and moderns speak of this divine principle of the art [i.e., inspiration]; but, as I have formerly observed, enthusiastic admiration seldom promotes knowledge. Though a student by such praise may have his attention roused, and a desire excited of running in this great career, yet it is possible that what has been said to excite may only serve to deter him. He examines his own mind, and perceives there nothing of that divine inspiration with which he is told so many others have been favored. He never travelled to heaven to gather new ideas; and he finds himself possessed of no other qualification than what mere common observation and a plain understanding can confer. Thus he becomes gloomy amid the splendor of figurative declamation, and thinks it hopeless to pursue an object he supposes out of the reach of human industry. (Reynolds, Third Discourse)

Look beyond “mere” inspiration. Idea, form and the desire to communicate: these three are the means by which creativity works. An awareness of their functions assists the Sub-Creator in ordering his creation, and acquiring the patience needed for mythopoesis.

(originally in Mythlore 36, Summer 1983) (revised 2005)

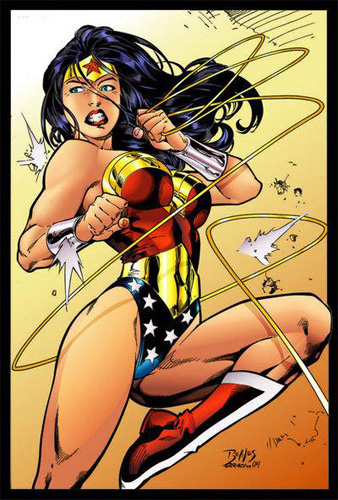

Every so often readers (and writers) comment on problems they have with the comic book character Wonder Woman.

Every so often readers (and writers) comment on problems they have with the comic book character Wonder Woman.

The Lasso of Truth also forces an unusual quality upon the nature of Wonder Woman. By using it, Diana can force a perpetrator to face aspects of his or her own nature that they have been denying. Even if she doesn’t use this power, its presence with her is a constant reminder of what she could do. It bestows a certain implacability to her character.

The Lasso of Truth also forces an unusual quality upon the nature of Wonder Woman. By using it, Diana can force a perpetrator to face aspects of his or her own nature that they have been denying. Even if she doesn’t use this power, its presence with her is a constant reminder of what she could do. It bestows a certain implacability to her character. Some of the factors that create this unsettling nature spring from how closely Wonder Woman’s character parallels that of the Greek goddess Nemesis. Nemesis was the daughter of Night, which places her in the realm of the mysterious and unaccountable. We have come to treat nemesis as a negative force, but she wasn’t such originally. She was all about keeping things in proper balance. She made sure virtue was rewarded and injustice was brought to balance. She is, in fact, the figure of Justice we see in courts these days; blind-folded for impartiality (she doesn’t care about your social status), holding both a sword and a balance scale — and she will use that sword to help put the scales in balance. Nemesis is very unsettling — and Wonder Woman, for similar reasons, carries the same effect.

Some of the factors that create this unsettling nature spring from how closely Wonder Woman’s character parallels that of the Greek goddess Nemesis. Nemesis was the daughter of Night, which places her in the realm of the mysterious and unaccountable. We have come to treat nemesis as a negative force, but she wasn’t such originally. She was all about keeping things in proper balance. She made sure virtue was rewarded and injustice was brought to balance. She is, in fact, the figure of Justice we see in courts these days; blind-folded for impartiality (she doesn’t care about your social status), holding both a sword and a balance scale — and she will use that sword to help put the scales in balance. Nemesis is very unsettling — and Wonder Woman, for similar reasons, carries the same effect. She’s “a babe,” a confident woman, beautiful and bold. And yet, Wonder Woman remains difficult to peg. That is, perhaps, part of her enduring power to fascinate us. We try to sort her out, to figure what makes her tick, because we don’t really want to deal with someone as completely committed to truth and justice as the Amazon princess is. She’s not some wild woman who needs taming, nor some insecure heroine who needs coaching. She is, as she has always been, Wonder Woman and something more than we expect.

She’s “a babe,” a confident woman, beautiful and bold. And yet, Wonder Woman remains difficult to peg. That is, perhaps, part of her enduring power to fascinate us. We try to sort her out, to figure what makes her tick, because we don’t really want to deal with someone as completely committed to truth and justice as the Amazon princess is. She’s not some wild woman who needs taming, nor some insecure heroine who needs coaching. She is, as she has always been, Wonder Woman and something more than we expect.

Let us be clear: the story-adventure of Up actually begins when Russell shows up on Carl’s doorstep insisting he has to help the elderly man. That is Carl’s Call to Adventure, and he’s not having any of it. (His Refusal of the Call makes for a bit of comedy: he sends the kid on a snipe hunt.) That is, structurally speaking, where the story starts.

Let us be clear: the story-adventure of Up actually begins when Russell shows up on Carl’s doorstep insisting he has to help the elderly man. That is Carl’s Call to Adventure, and he’s not having any of it. (His Refusal of the Call makes for a bit of comedy: he sends the kid on a snipe hunt.) That is, structurally speaking, where the story starts. Of course they fall in love. Their enjoyment of each other is its own adventure. Their dream of a real adventure is a shared dream, but not the real glue of their lives (though it will take Carl a while to understand that).

Of course they fall in love. Their enjoyment of each other is its own adventure. Their dream of a real adventure is a shared dream, but not the real glue of their lives (though it will take Carl a while to understand that). It is important for us to know that Carl is capable of love and that he does understand the call of adventure that has a hold on Russell. And that we are given the chance to love Ellie too, this gives us the powerful gift of wanting Carl’s adventure to succeed. We connect with the forces that drive him on, in a very powerful way.

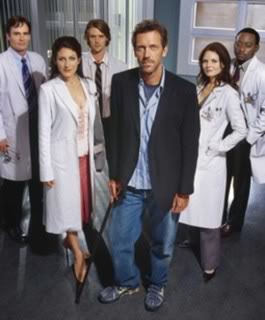

It is important for us to know that Carl is capable of love and that he does understand the call of adventure that has a hold on Russell. And that we are given the chance to love Ellie too, this gives us the powerful gift of wanting Carl’s adventure to succeed. We connect with the forces that drive him on, in a very powerful way. But House is also an example of what I call the “Divine Hero.” Now, this doesn’t mean that the Divine Hero has superpowers. It means that the hero comes from outside the community, bringing a boon to it. He is in the community, but not of it.

But House is also an example of what I call the “Divine Hero.” Now, this doesn’t mean that the Divine Hero has superpowers. It means that the hero comes from outside the community, bringing a boon to it. He is in the community, but not of it. Let’s start with McCoy. In this particular trinity of characters, he is firmly in the position of sidekick. Sidekicks are often Trickster archetypes, for their job is to puncture the excesses of the principal hero. Cranky McCoy frequently does this to Kirk and to Spock. When Kirk pushes for some outrageous solution, McCoy puts the brakes on. “Damn it, Jim! I’m a doctor, not a bricklayer!” He also relights the fire when Spock dampens things too much with logic. I read one critic who commented that McCoy was a bigot. One assumes the comment was inspired by McCoy’s comments about Spock as a “pointy eared hobgoblin.” But I think it is an error to call McCoy a bigot: he has no such reaction to other Vulcans or other aliens. This reaction is specific to Spock. It is another manifestation of his function as a Trickster, to puncture the excesses of Spock’s logic.

Let’s start with McCoy. In this particular trinity of characters, he is firmly in the position of sidekick. Sidekicks are often Trickster archetypes, for their job is to puncture the excesses of the principal hero. Cranky McCoy frequently does this to Kirk and to Spock. When Kirk pushes for some outrageous solution, McCoy puts the brakes on. “Damn it, Jim! I’m a doctor, not a bricklayer!” He also relights the fire when Spock dampens things too much with logic. I read one critic who commented that McCoy was a bigot. One assumes the comment was inspired by McCoy’s comments about Spock as a “pointy eared hobgoblin.” But I think it is an error to call McCoy a bigot: he has no such reaction to other Vulcans or other aliens. This reaction is specific to Spock. It is another manifestation of his function as a Trickster, to puncture the excesses of Spock’s logic. As a doctor, of course, McCoy is also a Transformer, changing the things around himself. But this is often secondary to his function as a Trickster. In the film, when McCoy first arrives on the scene, he transforms Kirk’s situation from being solitary to having a friend.

As a doctor, of course, McCoy is also a Transformer, changing the things around himself. But this is often secondary to his function as a Trickster. In the film, when McCoy first arrives on the scene, he transforms Kirk’s situation from being solitary to having a friend.

Kirk, however, is a Ruler. Although he frequently pushes the envelope of a circumstances (a manifestation of his being a Transformer and Trickster), he does pay attention to the skills of his subordinates. He delegates tasks appropriately.

Kirk, however, is a Ruler. Although he frequently pushes the envelope of a circumstances (a manifestation of his being a Transformer and Trickster), he does pay attention to the skills of his subordinates. He delegates tasks appropriately.