I’m going to add a new feature category to this blog, called “Musings” (to join “Mythic Motifs at Work” and “Writing Tips”). These will be more general considerations, rather than specific analyses or writing advice. It is inspired by the search strings that get used to bring people to my website (that is, both this blog and my main website — www.scribblerworks.us). The search strings often have interesting twists tot hem.

The one I’m musing on today was “how the Hero Quest affects society.”

“Interesting,” I thought.

Okay. So, first off, which “society” are we talking about here? The society inside the story, or the society of the audience? There wasn’t really a way of determining that from the search string, of course. So why not look at both?

So, let’s start with “inside the story”.

Inside the story, how does the Hero Quest affect society?

Let’s say that the “society” involved is, in terms of the Hero’s Journey, the Hero’s home or starting community. The one where his interests are engaged. Either he starts out as a misfit and has to go on his adventure in order to fit, or something is missing in the society and he has to go find it to repair the lack in the society.

The first possibility means that the Hero’s Quest takes someone who doesn’t fit in the community and changes that character to one who will be a benefit to the community. A ne’er-do-well who becomes a strong leader (Han Solo in Star Wars). The over-looked pigherder who becomes a king (Taran in Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain). A rogue computer programmer who frees others from machine mind-control (Neo in The Matrix). So the end of the Hero Quest in that case certainly has a positive effect on the society of the story.

The second possibility means that whether voluntarily or not, the Hero’s Quest will be a real benefit to the community of the story. If it is involuntary, our Hero may not have sought out the quest, but he will certainly see it to the end. Dr. Kimble (in The Fugitive), in trying to clear himself of a murder charge, discovers that a colleague has concealed the real (damaging) effects of a drug in order that he make a fortune. Kimble’s quest saves the medical community from disaster. In Deja Vu, an ATF investigator, thinking he will not be able to change the course of a large disaster instead focuses on trying to prevent one murder. Yet in doing so, he ends up preventing the large disaster, a definite benefit for the society in the story.

This reveals that even though the Quest itself may focus on an individual, there is a community in the background that will be affected. As the poet Donne put it, “No man is an island.”

So, what about the Society outside the story?

When we move to that level, it becomes a matter of why we tell stories at all. Soemtimes it is to relate events that have happened, so we won’t forget them. soemtimes it is to consider what we wish would happen. Sometimes it is to try and understand why a person would behave in a certain way. Sometimes it is to hold up a model of what we want to be like.

As a consequence, when we tell a story of a Hero’s Quest, we are, basically, trying to inspire ourselves. We want to be a resistant to peer pressure as the Hero in The Prisoner (the original, that is). We want to believe we can be as inspired and committed to our craft as Mozart is in Amadeus. We want to believe that we too can be as faithful in hardship as Sam Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings.

Indeed, in The Lord of the Rings, at a dark point in the quest Sam shares with Frodo, Sam muses about the stories he had heard and that fueled his imagination — and he takes heart and determination from them. He does not claim the high level of his “story-book” heroes, but rather that he be like them in even just a little way. And he succeeds.

That is what society outside the story gains — inspiration, moels, the belief that we can change and improve things around us. So… let the questing never end.

Feel free to comment here on the blog, or on my MESSAGE BOARD.

In creating a Secondary World, a Sub-Creator sets out on a journey into a new world. It is a journey into new places, where the

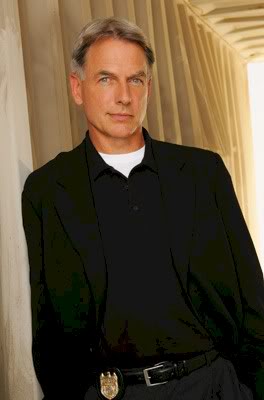

In creating a Secondary World, a Sub-Creator sets out on a journey into a new world. It is a journey into new places, where the  Which brings me to one of the best examples of a Father Figure currently running in popular culture: Leroy Jethro Gibbs on the show NCIS.

Which brings me to one of the best examples of a Father Figure currently running in popular culture: Leroy Jethro Gibbs on the show NCIS. As a Mentor, Gibbs uses his “strong, silent” manners to demonstrate to Timothy McGee and Ziva David how to be an excellent investigator. These two, for different reasons, have needed the instruction a Mentor can provide. And they have learned successfully from Gibbs.

As a Mentor, Gibbs uses his “strong, silent” manners to demonstrate to Timothy McGee and Ziva David how to be an excellent investigator. These two, for different reasons, have needed the instruction a Mentor can provide. And they have learned successfully from Gibbs. For Ziva, trained in espionage and assassination, learning to investigate and interview has run counter to her impulses. But because Gibbs by every indication shows her that he believes her capable of the new methods and expects her to act on them, she learns.

For Ziva, trained in espionage and assassination, learning to investigate and interview has run counter to her impulses. But because Gibbs by every indication shows her that he believes her capable of the new methods and expects her to act on them, she learns. But Gibbs has also done the same for Tony: during a case in which Gibbs had given Tony the lead, Tony becomes so frustrated that he begins verbally abusing the team. Gibbs takes Tony aside and tells him he had been doing a good job … up to that point. The fact that this is a “priestly” action is shown by the fact that Gibbs addresses DiNozzo as “Anthony,” something he almost never does. Tony is both chastened and encouraged by this.

But Gibbs has also done the same for Tony: during a case in which Gibbs had given Tony the lead, Tony becomes so frustrated that he begins verbally abusing the team. Gibbs takes Tony aside and tells him he had been doing a good job … up to that point. The fact that this is a “priestly” action is shown by the fact that Gibbs addresses DiNozzo as “Anthony,” something he almost never does. Tony is both chastened and encouraged by this. As the boss of the team, Gibbs is in fact the Ruler of them all. But one of the duties of the Ruler is to command the discipline of his subjects, and this is the need Gibbs fills for DiNozzo and Agent Kate Todd. Although Tony is actually a good investigator, his own impulses are to flake off, chasing pretty women or playing games. Gibbs enforces discipline and so gets excellent work out of Tony.

As the boss of the team, Gibbs is in fact the Ruler of them all. But one of the duties of the Ruler is to command the discipline of his subjects, and this is the need Gibbs fills for DiNozzo and Agent Kate Todd. Although Tony is actually a good investigator, his own impulses are to flake off, chasing pretty women or playing games. Gibbs enforces discipline and so gets excellent work out of Tony. As a Protector, we see Gibbs protecting both Abby and Ziva. When Ziva was framed for the assassination of someone under FBI protection, it is to Gibbs (and not her own father) that she turns to, to get her out of it. And he does.

As a Protector, we see Gibbs protecting both Abby and Ziva. When Ziva was framed for the assassination of someone under FBI protection, it is to Gibbs (and not her own father) that she turns to, to get her out of it. And he does.

The sky is a jewel-like blue. The broad moor hides its colors in a dark blanket. On the eastern horizon, dawn pours a cream and pink light into the air. And there silhouetted against the growing day, pace a line of figures.

The sky is a jewel-like blue. The broad moor hides its colors in a dark blanket. On the eastern horizon, dawn pours a cream and pink light into the air. And there silhouetted against the growing day, pace a line of figures.