Down the ages there have been two important Types of characters in storytelling: heroes and heroines. The Hero was the character the storyline followed, relating his trials and victories. The Heroine was the character the Hero loved, won, and came home to. Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces (Princeton University Press: 1973) explicates what he calls the “monomyth” of the Hero, the pattern of the Hero’s quest and the type of events which he encounters. Much, indeed, has been written on Heroes. Much less has been said about Heroines. Ralph Tymns in The Double in Literature (Bowes & Bowes: 1949) makes these observations of two Types of the Heroine:

Down the ages there have been two important Types of characters in storytelling: heroes and heroines. The Hero was the character the storyline followed, relating his trials and victories. The Heroine was the character the Hero loved, won, and came home to. Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces (Princeton University Press: 1973) explicates what he calls the “monomyth” of the Hero, the pattern of the Hero’s quest and the type of events which he encounters. Much, indeed, has been written on Heroes. Much less has been said about Heroines. Ralph Tymns in The Double in Literature (Bowes & Bowes: 1949) makes these observations of two Types of the Heroine:

The blue-eye, fair-haired, light complexioned one is the Fair Maiden, alias the Persecuted Maiden, the Virgin, the Saint, the Pale Lady, the Good Woman, the Nice Girl, the Marriageable Young Lady. Her darker counterpart is the Femme Fatale, alias the Temptress, the Vamp, the Sinner, the Dark Lady, the Bad Woman, the Naughty Girl, the Trollop. Sometimes she is called Mistress or Prostitute or Even or Whore of Babylon, depending on circumstances. (DL, p. 126)

This is, of course, an extreme and simple analysis of the two Types of Heroine, for both have positive and negative presentations. Additionally the Heroine can appear in the three-form possibilities of Maiden, Matron and Hag. So often, for the Storyteller, the Heroine serves to depict some element or quality the Hero needs to deal with. Indeed, Maud Bodkin observes in Archetypal Patterns in Poetry (Oxford University Press: 1963) that

It is in the process of fantasy that the contemplated characters of things are broken from their historical setting and made available to express the needs and impulses of the experiencing mind. (APP, p. 7)

If the Sub-Creator is using his Heroes and Heroines in order to examine the nature of something, then perhaps the gender of the characters has little to do with their function. Perhaps it is only tradition that sets the pattern.

If gender is not important to the functions of Heroes and Heroines, what qualities are important? Campbell calls his perception of the Hero a “monomyth”, which indicates a singular quality tot he function of the Hero, no matter what personality is given the Hero. Campbell’s study deals with the elements of the Hero’s quest and its progress. By this we can determine that the Hero represents the quality of action. Using Tymns’ observations, we can begin to perceive the quality represented by the Heroine, a quality which we might call the “essence”. The Heroine usually represents for the Hero the essences of love or wisdom or socialization.

The Hero’s quest is the quest of Self, and traditionally the Hero’s union with the Heroine at the end signified reintegration in Society. The Hero’s quest springs up in isolation, alienation and exile, and if in the story it is an isolation, from Society, in the character it is an isolation from the Self. Campbell observes

From the standpoint of the way of duty, anyone in exile from the community is a nothing. From the other point of view, however, this exile is the first step of the quest. Each carries within himself the all; therefore it may be sought and discovered within. The differentiations of sex, age, and occupation are not essential to our character, but mere costumes which we wear for a time on the stage of the world. The image of man within is not to be confounded with the garments. (HTF, p. 385)

The Quest is an inner one, and as Campbell points out, the form of its main character is merely a costume for the Self.

It might be more helpful, then, to call the two functions of the Quest the Quality of Action and the Quality of Essence, rather than Hero and Heroine, for in recent years, the force of tradition has been weakening. In many recent works, female characters have been assuming the role of “hero”, the quester, the active character. Tradition does still hold sufficient sway to keep the other reversal at a minimum: the part of the passive, “essential” anchor is not yet often given to male characters.

It might be more helpful, then, to call the two functions of the Quest the Quality of Action and the Quality of Essence, rather than Hero and Heroine, for in recent years, the force of tradition has been weakening. In many recent works, female characters have been assuming the role of “hero”, the quester, the active character. Tradition does still hold sufficient sway to keep the other reversal at a minimum: the part of the passive, “essential” anchor is not yet often given to male characters.

What could be provoking this change in the function assigned to female characters? It is not simply the growing social consciousness of the equality of the sexes. By looking at the nature of the quest and not its characters, we may find a key. Could it be that alienation is so pervasive a factor in modern life that resocialization is deemed irrelevant? Could it be that the quest for Self takes all the importance of meaning in a story, and that therefore female characters (who in addition to traditionally representing “essential” qualities also often represent the sub-conscious) are better suited to the modern quest mode? What ever the actual cause, any Sub-Creator would do well to remember the functions of Hero and Heroine, whether the “Hero” is masculine or feminine. Randal Helms, in Tolkien’s World (Houghton Mifflin: 1974) makes these observations of the handling of the Heroes in modern works:

A hero is the expression of a culture’s ideals about itself, and our ideals about ourselves have all been punctured. Cultural ideals are formulated and understood most efficiently in myths, and we have lost the ability to participate wholeheartedly in mythic belief, lost in fact the key to respond to our culture’s central mythic system…. Most contemporary heroic fantasy is vulgar and debasing – struggle against will, rescue of good – but because those themes are unsupported by a resonant image of man: they lack a vital superstructure of ideas. (TW, p. 150)

In order to avoid this hollow vulgarity, then, the Sub-Creator must remember that his Hero and Heroine are not simply characters moving through events, but that they are qualities that have meaning for his readers. Although few Authors begin to form their story by focusing on meaning of what they wish to say, they should not ignore it. The object of the Hero’s quest – on the level of the story’s (meaning), not its events – is internal growth, to achieve the spiritual balance which is often represented in the figure of the Heroine. The Heroine serves to call the Hero onward to the completion of the quest.

Admittedly, when one is discussing Types in literature, the exceptions leap to mind, the characters who do not precisely fit the pattern. There are the Heroines who are active participants in the journey of the quest, not simply the reward waiting at the end of the quest, not simply the reward waiting at the end of the trials; there are the Fair and Dark Heroines who break their Type; the Heroes who skip elements in the quest or who do not achieve self-awareness and resocialization. But these are “made available to express the needs and impulses of the experiencing mind” (APP, p. 7).

Campbell has this to say of the meaning of the quest, unfractured by being separated into Hero and Heroine:

The aim is not to see, but to realize that one is, that essence; then one is free to wander as that essence in the world. Furthermore; the world too is of that essence. The essence of oneself and the essence of the world; these two are one. Hence separateness, withdrawal, is no longer necessary. Wherever the hero may wander, whatever he may do, he is ever in the presence of his own essence – for he has the perfected eye to see. There is no separateness. Thus, just as the way of the social participation may lead in the end to a realization of the All in the individual, so that of exile brings the hero to the Self in all. (HTF, p. 386)

How the Author handles his characters, the depth of recognition he shows as to (what) his characters represent in the tale, can affect how honestly and freely he deals with them in the telling of the story. The Author’s understanding can give the Hero and Heroine (for those who are filling their functions) the free rein they need in order to achieve the quest. But a failure – whether conscious or sub-conscious – to understand the Qualities of Hero and Heroine will only cripple the characters. The stronger grasp an Author’s awareness has of this truth, the surer touch it will have in breathing life into the questers, the Heroes and Heroines.

(first published in Mythlore 43, Autumn 1985; revised 2007)

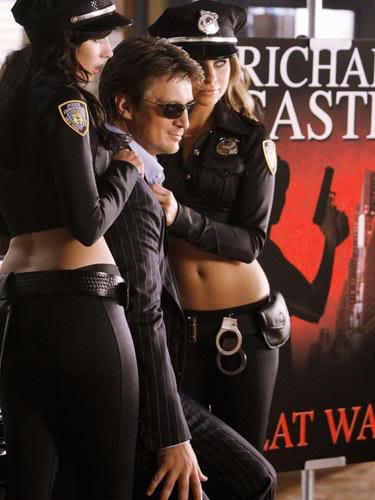

Most obvious to start with is Castle’s shape as a best-selling author. He’s not pretending in this shape: he works for it and has a string of titles that justify the attention he gets in this shape. He uses it frequently to evade intrusion into his personal life (including warning his daughter against visiting the “fan websites”). This shape gives him entre to many special areas of life.

Most obvious to start with is Castle’s shape as a best-selling author. He’s not pretending in this shape: he works for it and has a string of titles that justify the attention he gets in this shape. He uses it frequently to evade intrusion into his personal life (including warning his daughter against visiting the “fan websites”). This shape gives him entre to many special areas of life. One of those “special areas” is that of “High Society.” In that arena, Castle turns into the “wealthy, eligible bachelor” who mixes with the upper crust of New York social life. Again, his presence there is not a pretense. He knows the functions (such as the quarterly fund-raising benefits for a city dance company) and is considered a legitimate member of those circles. In this shape, Castle can give Beckett access to information she might not get in her own guise of “detective.” And note: she has to change shape with him to access that knowledge.

One of those “special areas” is that of “High Society.” In that arena, Castle turns into the “wealthy, eligible bachelor” who mixes with the upper crust of New York social life. Again, his presence there is not a pretense. He knows the functions (such as the quarterly fund-raising benefits for a city dance company) and is considered a legitimate member of those circles. In this shape, Castle can give Beckett access to information she might not get in her own guise of “detective.” And note: she has to change shape with him to access that knowledge. He does, of course, put on some guises for the mere fun of it. But the fun and playfulness are actually necessary features for a well-balanced psyche. He dresses up for Halloween, he plays fencing games with his daughter, he makes silly bets with the detectives. Is he hiding a truth in this guise? Perhaps. Not one for himself, but rather one that Beckett needs. She needs the playfulness he brings to counter the real emotional weight of the work she does investigating murders.

He does, of course, put on some guises for the mere fun of it. But the fun and playfulness are actually necessary features for a well-balanced psyche. He dresses up for Halloween, he plays fencing games with his daughter, he makes silly bets with the detectives. Is he hiding a truth in this guise? Perhaps. Not one for himself, but rather one that Beckett needs. She needs the playfulness he brings to counter the real emotional weight of the work she does investigating murders. One of the realities of life that Castle deals with in the series is the fact that he is the single parent of a teen-aged girl. He makes comedy out of it by putting on the exaggerated aspect of the “Prom Dad” (where the father of the girl frightens the date into behaving himself). But even though Rick exaggerates it, it is also the reality. He is not a neglectful parent.

One of the realities of life that Castle deals with in the series is the fact that he is the single parent of a teen-aged girl. He makes comedy out of it by putting on the exaggerated aspect of the “Prom Dad” (where the father of the girl frightens the date into behaving himself). But even though Rick exaggerates it, it is also the reality. He is not a neglectful parent. Indeed, his shape as “Parent” is one of Castle’s truest forms, revealing the truth about his personality underneath all his playfulness, evasions and flippancy. He is genuinely concerned about how Alexis proceeds in life. And likewise, he does not conceal much from her — except perhaps the depth of his feelings for Beckett. She, however, is a wise child, practiced in learning the secrets of a Shapeshifter and she already has an awareness of the connection between the adults.

Indeed, his shape as “Parent” is one of Castle’s truest forms, revealing the truth about his personality underneath all his playfulness, evasions and flippancy. He is genuinely concerned about how Alexis proceeds in life. And likewise, he does not conceal much from her — except perhaps the depth of his feelings for Beckett. She, however, is a wise child, practiced in learning the secrets of a Shapeshifter and she already has an awareness of the connection between the adults. But along with being a father, one of Castle’s most essential shapes is that of a researcher. He has been shown doing careful research for his books. He knows how to ask telling questions and he knows where to find sources. When Beckett’s cases take them into strange territories, Castle’s research abilities (either past or present) give the pair special knowledge they need to solve the current mystery.

But along with being a father, one of Castle’s most essential shapes is that of a researcher. He has been shown doing careful research for his books. He knows how to ask telling questions and he knows where to find sources. When Beckett’s cases take them into strange territories, Castle’s research abilities (either past or present) give the pair special knowledge they need to solve the current mystery. “Style” is a slippery word when one comes to consider writing of any sort. Yet it seems to become a fighting word when one turns to fantasy. It is deeply felt by many writers and readers of fantasy that

“Style” is a slippery word when one comes to consider writing of any sort. Yet it seems to become a fighting word when one turns to fantasy. It is deeply felt by many writers and readers of fantasy that