I’ll start by saying I’m not familiar with the source material, or the earlier drafts of the film scripts. You could say I’m disengaged from earlier versions. I’m just working from what was achieved in the theatrical film.

World War Z had crucial elements that should have shaped the film for success. So what went wrong with it? Appealing star, apocalyptic disaster, plenty of action – all elements that should have hooked the audience and kept them hooked.

The Galahad Grail Quest

First off, let’s consider the basic nature of the quest story. This particular story fits the pattern for a Galahad Grail Quest.

Grail Quests are specialized types of quests that involve the relation between the question hero and the community around him. The elements of the Galahad Quest are these:

- The hero is on a quest of fulfillment of the self.

- The hero is destined to succeed.

- The hero heals the king before he completes the quest.

- The land is healed.

- The hero achieves the goal of the quest.

In a Galahad Quest, the hero often enters a situation he is not personally connected to, usually because he has a personal quest of his own. The king need not be an actual person; the figure is simply the key identifier of whatever ails “the land” of the story.

Does Gerry Have a Personal Quest?

This is where World War Z starts out well and then goes off the rails. During the first portion of the film, Gerry Lane (Brad Pitt) focuses on keeping his family safe from the fast-spreading zombie plague. The opening sequence shows Gerry’s special qualities: keen observation and deduction, and superior adaptive survivor skills. It sets Gerry up well for the primary quest of the film: finding the way to stop the zombie plague.

This is where World War Z starts out well and then goes off the rails. During the first portion of the film, Gerry Lane (Brad Pitt) focuses on keeping his family safe from the fast-spreading zombie plague. The opening sequence shows Gerry’s special qualities: keen observation and deduction, and superior adaptive survivor skills. It sets Gerry up well for the primary quest of the film: finding the way to stop the zombie plague.

The major story problem begins when Gerry is sent on the quest to find the origins, nature, and answer to this zombie plague. First off, he is sent. He is selected as the best investigator available, the one most likely to succeed in this quest to save the human race. Certainly, the stakes are compelling: save the world. But emotionally, Gerry’s drive is to save his family.

The major story problem begins when Gerry is sent on the quest to find the origins, nature, and answer to this zombie plague. First off, he is sent. He is selected as the best investigator available, the one most likely to succeed in this quest to save the human race. Certainly, the stakes are compelling: save the world. But emotionally, Gerry’s drive is to save his family.

And that emotional compulsion leads to the second problem in the story. When he begins the quest, his family is safe. That is why he agrees to go at all. Oh, the storytellers put in a touch of hazard: as long as Gerry makes progress in the quest, his family may stay aboard the command ship at sea. But if he gives up or fails, because they are “non-essential personnel” they would be transferred to a remote refugee camp – with the implication that the camps might be over-run eventually. This option is presented as ruthless necessity – they are “non-essential.” But looked at from the outside, any un-infected humans would in fact be absolutely essential for the survival of the human race, no matter what their skill set was.

So, the emotional stake for Gerry came across as a dud. He’ll do it because he is noble and all that. In short, he will do it because, hey, he’s the hero of this story. (He is destined to succeed.)

The Progress of Gerry’s Quest

Off he goes on the quest. First stop: Korea. He learns about the first instances, and that the zombies are attracted to noise. What he learns there sends him to Israel, hopefully to consult a well-known doctor there. In Israel, he finds they have built a huge, secure compound that, to that point, has kept the zombies out.

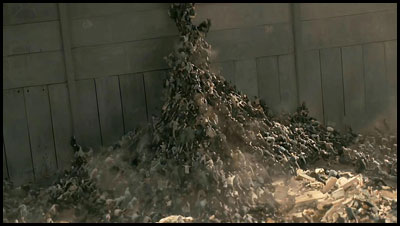

But does he tell the Israeli doctor that the zombies are attracted to noise? No, he does not. At this point, the story starts losing the audience. If Gerry is to save the world, why not tell these people the first important survival tip he has learned: keep quiet. He doesn’t warn anyone – until the refugees in the compound start singing and dancing – making noise. The zombies swarm over the wall. As the zombies swarm, Gerry and the doctor realize that the zombies ignore anyone diseased and dying. They speculate that a major infectious disease would help save the humans. The Israeli doctor tells Gerry his best bet is to find the right virus and antidote is an isolated lab in Wales.

But does he tell the Israeli doctor that the zombies are attracted to noise? No, he does not. At this point, the story starts losing the audience. If Gerry is to save the world, why not tell these people the first important survival tip he has learned: keep quiet. He doesn’t warn anyone – until the refugees in the compound start singing and dancing – making noise. The zombies swarm over the wall. As the zombies swarm, Gerry and the doctor realize that the zombies ignore anyone diseased and dying. They speculate that a major infectious disease would help save the humans. The Israeli doctor tells Gerry his best bet is to find the right virus and antidote is an isolated lab in Wales.

Off Gerry goes again, rescuing Israeli soldier Segen along the way – because he has deduced that the bite of the zombies infects the blood stream. Segen gets bitten on the hand, and Gerry immediately cuts off her lower arm, hoping he has stopped the spread in her system. He counts off the seconds and yes, it has worked.

Off Gerry goes again, rescuing Israeli soldier Segen along the way – because he has deduced that the bite of the zombies infects the blood stream. Segen gets bitten on the hand, and Gerry immediately cuts off her lower arm, hoping he has stopped the spread in her system. He counts off the seconds and yes, it has worked.

The remainder of the action involves getting to the lab, getting to the vault with the viruses and antiviruses, and getting these out to the rest of the humans, thus stopping the virus.

And of course, Gerry succeeds.

So why did the movie feel so flat?

The Disengaged Problems with World War Z

The problems in the storytelling are two-fold.

First, the external problem as set up is nearly insurmountable. Although it takes a red blood cell 20 seconds to circle the whole body, the story shows us that in a mere 12 seconds after being bitten the victim dies. The zombie plague successfully infects too fast for most story options. There is almost no doubt that a bite means death. Gerry’s hack job is the only demonstrated evasion of that and it comes late in the story. The speed of the plague mechanism removes the suspense of will-they-or-won’t-they become victims. And Segen’s rescue is played as absolute when she doesn’t die after the 12-count.

The second major problem is the emotional connection of the audience with Gerry – or rather, the lack of it. He’s an observer, primarily, and that makes the character distanced from the audience from the start. It isn’t that Observer characters are completely unappealing, they are not. Famous and popular Observer characters would be Sherlock Holmes or Star Trek’s Mr. Spock. But both of those characters are mediated by a more emotive character that the audience connects to. Gerry, however, is basically all alone. His family is left behind early, and Segen, other than being a fellow survivor, has no emotional connection to him. So there is no emotional mediator for the audience, no one who can reflect Gerry’s internal emotions and challenges.

For the audience, Gerry Lane (no matter how well played by Brad Pitt) is about as emotionally engaging as the zombies he is trying to stop. There’s plenty of action and spectacle to the story, but considering the global threat, the emotional ride is rather flat.

For the audience, Gerry Lane (no matter how well played by Brad Pitt) is about as emotionally engaging as the zombies he is trying to stop. There’s plenty of action and spectacle to the story, but considering the global threat, the emotional ride is rather flat.

What Could Have Been Done?

Assuming the premise of the zombie plague and its solution remained the same – in the first act, when the family is escaping, have one of the Lane’s daughters get bitten and they have to leave her (she’s now dead and a zombie). This puts a high emotional charge between Gerry and his wife. When Gerry is sent on the quest, his wife goes with him, as his working partner (easy enough to give her a backstory and expertise that matches his). In Israel, instead of rescuing Segen, who has no emotional connection to Gerry, have it be Gerry’s wife that must be saved by lopping off part of her arm. These changes would have engaged the audience far more, for in addition to the global question of stopping the zombies, there would be the emotional question of whether the relationship between Gerry and his wife would survive.

An engaging story has to intensely make the audience not want to be a zombie. To do that, the main character they are following has to be much more than an emotionally disengaged zombie.