March 2014 saw the release of director Darren Aronofsky’s film, Noah, to much controversy and discussion. For many Christian members of the audience, the fact that a story from the Bible was being presented by an avowed atheist did not bode well.

Let us consider again the term “myth.” Many people use that word in a derogatory fashion, to mean made-up stories about non-existent supernatural entities, stories that do not deserve credulity or belief. They might be engaging as stories, but not as anything of genuine value. This outlook presupposes no supernatural entities, and also dismisses much of the power of meaning in storytelling. But myth is always about meaning. The point about a mythic story is not usually whether or not it is also historical fact, but rather what it means. For Christians, they hold that the stories of their myth are also historical fact. So, when someone plays fast and loose with a Biblical story, they have problems with that.

But it’s just a movie. Will it really make that much of a difference to the “real myth”? Probably not. So let’s step back and just consider the film story as a story in itself. In fact, let’s first look at a couple of other instances where a filmmaker made changes to a myth.

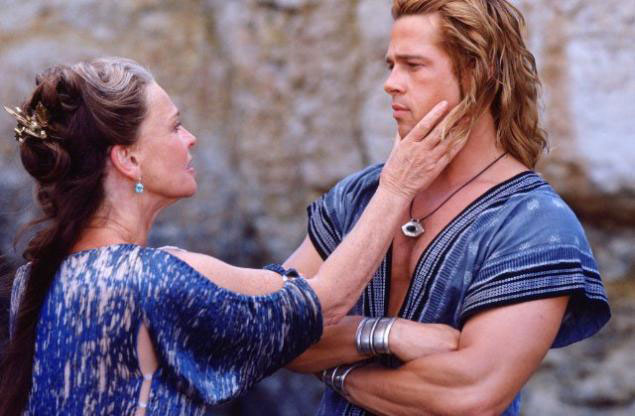

In 2004, director Wolfgang Petersen released Troy, a version of the story of Achilles and the Trojan War, adapted from Homer’s The Iliad. We can assume that there are not many alive in the present who are invested in the reality of the gods of Olympus. In Homer’s story, Achilles, the greatest of the Greek heroes, can make or break the war of the Greeks against Troy.

Petersen’s film stays pretty close to the nature of Homer’s tale. It respects the source materials and its point about the cost of heroism. However, the director presents the story without any overtones of the supernatural. Which makes for an interesting choice regarding Achilles himself, mainly because he is the son of a goddess.

Thetis is a sea goddess. In the mythic story, it was predicted that her son would be greater than his father. So, even though Zeus was enamored of her, he feared the prophecy and married her off to a mortal. Achilles was the child of that union.

Petersen’s film skims over this divine heritage. Although we first see Thetis wading in water, collecting shells, nothing is done to indicate that she is anything more than a mortal woman. And it is in a conversation with his mother that Achilles hears the declaration of his future as hero: he can refuse to go to war, live a long life with love and family, die and be forgotten or he can take part in this war, fight gloriously, and die soon, but his name would last forever. He chooses the latter.

Petersen dismisses the supernatural element of the story of Troy. But he leaves the piety of the characters intact and respected. Achilles’ attack on the temple of Apollo appalls his men. In the script, Achilles is given a single line that implies personal knowledge of the true natures of the gods. That is as close as the film gets to referencing any possible supernatural elements.

Petersen keeps his vision of the story focused on heroism and its nature, on the price of glory. Although he stays true to the meaning of the original myth, he has stripped it of the supernatural, without warping the piety of the characters.

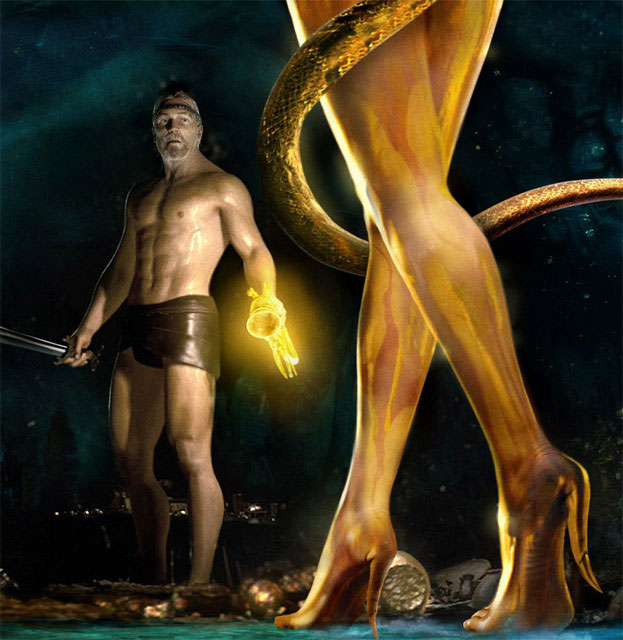

Another film that makes changes to an established myth is 2007’s Beowulf. In a script written by Neil Gaiman and Roger Avary, the filmmakers present a version of the story that runs counter to its source material.

I have to admit to being personally invested in the source material. I did my Masters thesis on the poem. I feel very strongly about what the story is about: the portrayal of the ideal hero.

However, the filmmakers chose to take a different approach to the material. In their hands, Beowulf is not quite the hero the source material makes him out to be. He lies. Additionally, King Hrothgar is a drunken fool, not a wise but indecisive lord.

Even more, Grendel is presented as a pathetic monstrosity, and his mother a magical seductress instead of a homicidal slayer.

Now, although I may disagree with the film as a faithful adaptation of a story I love, and although I’m not keen on stories where heroes turn out to be anything but heroic, I will admit that these storytellers stayed consistent with the story version they were telling. They kept their world-building true to itself. World-building means the elements that make up the setting and context of a story: the beliefs of the characters, the issues that matter to them, the rules they live by and the rules that are the declared values of the story. The film Beowulf does that. I didn’t particularly care for the choices, but the filmmakers played fair with their choices.

So what of Aronofsky’s Noah?

Part of the problem with Noah is that it does not clearly define the rules of the world of the story. Instead, it coasts on the audience expectation of a traditional definition of what this mythology presents. He shows us Eden and the temptation of Adam and Eve.

Except….

We are shown Paradise at a distance. We are not engaged in its nature by being brought close in to experience it. Secondly, the Edenic pair are luminous beings with indistinct features. How are we to identify with them?

Then the snake comes along, shedding its skin before approaching Eve. We see the Adam figure bend down to pick up the snakeskin. Why? We’re never told. And that is a problem in the storytelling, because that snakeskin becomes an important Maguffin later. It apparently becomes a magical talisman of the “righteous” line of Seth, used in a blessing ritual. Why? We’re not told.

It looks like a cross between a pomegranate and a red bell pepper – and it pulses like a beating heart. Why would anyone touch it let alone pick it and eat it?

The audience, who have not been clued in on the meaning this talisman is supposed to have to the characters, is left to make their own interpretation of what they are seeing – and they are likely to go with the traditional story. In that version, the snake and the temptation of Adam and Eve are evil events, leading the pair to be cast out of Eden. So why is the skin of the Tempter a precious talisman? We are not told. And because we are not told this crucial bit of information, we are kept a crucial distance from our main character. Why should we care that the talisman is stolen from Noah’s family?

Early in the story we see Noah confront men who have been pursuing an animal to kill and eat it. He stands up to them, beating them. One of them asks the man who is about to kill him (Noah) what he wants. Noah says “Justice.” The problem with this is that these men have no apparent connection to the men that killed Noah’s father, so killing them has no connection with gaining justice for the murder of his father. Instead, we are to assume that Noah wants justice for the animal that was killed.

This is the key to Aronofsky’s story. Human life is not what is of value: it is the animals and plants that are of primary value.

Okay, fine. If that is how the world of the story works. But again, that distant visual we were given of Eden is not enough to engage us emotionally in the devastation of nature. We are promptly plunged into desolate landscapes, where there is little vegetation, and it has to be carefully protected. We see Noah scolding one of his young sons for plucking a flower because it was beautiful.

But here’s where the world-building of the film fails. If animal life is so precious, why do Noah and his family have leather footgear? And if vegetation is so scarce, what feeds the animals enough to produce coats for shearing to make the yarns that are so finely woven and knitted for their wardrobes? Where are those sheep?

The filmmakers fail to convince the audience because they haven’t worked out these key logical points. The only animal we see clearly and might emotionally invest in was the one killed early in the story. Unfortunately, it looks like a cross between a whippet dog and a pangolin. We don’t know what it is, so other than its pathetic wound, we’re disconnected from it. That and the little meadow flower are all that are used to engage us in the stakes the movie says are important: that plants and animals are more important than other human beings. Unfortunately, they are too slight for the burden, so the script requires that Noah say this time after time after time. It thus breaks one of the earliest rules every screenwriter is given: show, don’t tell.

So, what have these failures in the basic storytelling to do with the changes in the mythology? It’s possible that with a bigger visual imagination, Aronofsky could have convinced the audience (for the duration of the film at least) that plants and animals are more valuable than humans. But instead, for the crucial plot point of saving the animals, Aronofsky shows us that the story’s god sends Noah a magical seed that sprouts instantly into a growing forest. This lush forest, however, gets no protection from Noah, but instead, a chunk of it is cut down to build the Ark. So, it’s apparently okay with this wrathful god that protecting one aspect of nature (the animals) may be accomplished by destroying another aspect (the forest).

You lost me there, Darren.

The story is not consistent with its own mythos.

With Beowulf, I did not like or agree with the story changes made, but enjoyed the film as a thing in itself because it was at least consistent with itself. With Troy, dropping the supernatural from the story was made to work, making it entirely human without denigrating the piety of the characters. But with Noah, we’re not given a compelling experience of the value we are expected to root for: the protection of nature. Instead we are dragged along with an obsessive man who possesses only meager charm.

I don’t have to worry about what Noah does or does not say about faith in a supernatural deity. It fails to communicate the emotional power of the stakes it declares to be important. If the audience cannot feel and experience the stakes (and we don’t in Noah), we’re not really invested in the hero’s success or failure – or the film’s. We’re just along for the ride.

And this ride is no fun at all (except for some disconnected humorous moments with Anthony Hopkins’ Methuselah). Iceland (where they shot it) is starkly beautiful, though.