A friend recently recommended the works of Annie Dillard to me, and so I began reading The Writing Life. In this particular book she describes in vignettes her experiences of the labor of writing, of doing the work (and some of the ways her own mind distracts her). At one point, she inclues the following passage —

A well-known writer got collared by a university student who asked, “Do you think I could be a writer?”

“Well,” the writer said, “I don’t know. … Do you like sentences?”

The writer could see the student’s amazement. Sentences? Do I like sentences? If he had liked sentences, of course, he could begin, like a joyful painter I knew. I asked him how he came to be a painter. He said, “I liked the smell of the paint.”

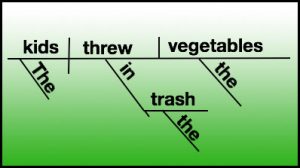

Yes, I borrowed this graphic.

The passage caught my attentnion with its truth. I love sentences. I love short sentences. I love medium lengthed sentences. I love sentences which sprout branches and provide nesting for warbling turns of phrase. I went through a period whee I was so in love with sentences that I drenched them in incense and clothed them in purple silk. Sentences that bounce; sentences that slither; sentences afflicted with alliteration; sentences condemned to pun-ishment. I like sentences.

A good craftsman in any art loves and takes care of his tools. What maintainence is needed for the writer, then? How do we take care of our tools?

A good craftsman in any art loves and takes care of his tools. What maintainence is needed for the writer, then? How do we take care of our tools?

We go back to basics, for one thing.

(Pardon me for the next bit of showing off: I’m a medieval scholar, I can’t help it. It’s part of what I know.)

The medieval philospher Boethius wrote a book titled The Consolation of Philosophy. Its title is pretty up-front about the book’s intention. Boethius wrote it while in prison facing a death sentence. But if you think (judging by the title) that it is an entirely dry treatise, you would be wrong. Boethius had a sense of humor. He opens the book describing himself languishing inprison, in the company of the muses of poetry, nubile young women who are cuddling and cooing over him, exclaiming how awful it is that he’s in prison and how undeserved this fate is. He’s still facing death, of course, but the company is soft. Then, instrides the bright, beautiful and stern Sophia (that is, Philosophy herself). She heaps scorn on the muses of poetry, driving them out, calling them “strumpets.” She coolly looks Boethius over, tells him he’s a mess, that he’s forgotten his first love – herself – and that he needs to go back to the basics. And then she launches into a lecture about grammar, in Ciceronian prose (which has to be, pretty much, the most precise use of Latin grammar to be found).

The medieval philospher Boethius wrote a book titled The Consolation of Philosophy. Its title is pretty up-front about the book’s intention. Boethius wrote it while in prison facing a death sentence. But if you think (judging by the title) that it is an entirely dry treatise, you would be wrong. Boethius had a sense of humor. He opens the book describing himself languishing inprison, in the company of the muses of poetry, nubile young women who are cuddling and cooing over him, exclaiming how awful it is that he’s in prison and how undeserved this fate is. He’s still facing death, of course, but the company is soft. Then, instrides the bright, beautiful and stern Sophia (that is, Philosophy herself). She heaps scorn on the muses of poetry, driving them out, calling them “strumpets.” She coolly looks Boethius over, tells him he’s a mess, that he’s forgotten his first love – herself – and that he needs to go back to the basics. And then she launches into a lecture about grammar, in Ciceronian prose (which has to be, pretty much, the most precise use of Latin grammar to be found).

Grammar? Seriously?

But yes.

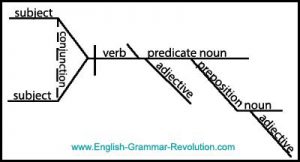

Do your descriptive phrases actually attach themselves to their proper subject? Do your pronouns actually have designated antecedants?

Yes, it seems boring to think about grammar once you’ve gotten past your middle school years. But it is part of the writer’s tool chest. And if you don’t keep the tools clean, the day could come when you find them rusted over, broken and useless.

I also love words. I love the music and rhythm of words. I love knowing their meanings. I love using them in unexpected ways, ways that grow from their meanings naturally.

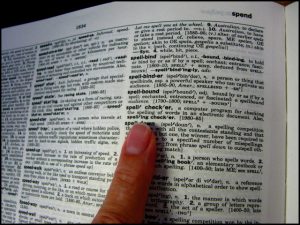

And I cringe when I encounter words used badly, words misapplied to the task at hand. Recently, I encountered such a misapplication in the work of an aspiring writer. The author had a passage of a group of people discussing a possible route they were to take, and in the midst of the discussion, he had one chaacter indicate a particular path, then “he alleged.” Ouch. In point of fact, the character had not “alleged” anything, he had merely made a statement of fact. On top of which, nothing in the discussion involved any implication of intent to speak untruthfully on any character’s part. I suspected that the author had simply consulted a thesaurus for alternatives to “said” and selected one without double checking its meaning.

And I cringe when I encounter words used badly, words misapplied to the task at hand. Recently, I encountered such a misapplication in the work of an aspiring writer. The author had a passage of a group of people discussing a possible route they were to take, and in the midst of the discussion, he had one chaacter indicate a particular path, then “he alleged.” Ouch. In point of fact, the character had not “alleged” anything, he had merely made a statement of fact. On top of which, nothing in the discussion involved any implication of intent to speak untruthfully on any character’s part. I suspected that the author had simply consulted a thesaurus for alternatives to “said” and selected one without double checking its meaning.

Do you love sentences? If you don’t, why do you want to write? What is it you think you are doing in writing, if you don’t have an affection for your basic tools?