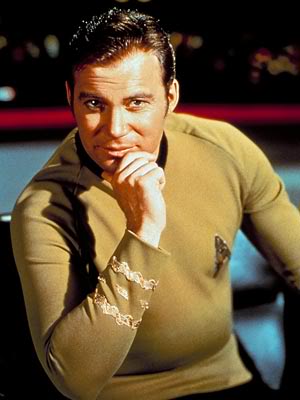

The release of the 2009 Star Trek movie re-sparked my interest in the character archetypes of Kirk, Spock and McCoy. I made some initial comments about them as a guest blogger on Colleen Doran’s blog. But that was comparing Kirk and Picard.

A well constructed character will have at least one archetype at the core. When multiple archetypes are blended, you can create very interesting dynamics.

Let’s start with McCoy. In this particular trinity of characters, he is firmly in the position of sidekick. Sidekicks are often Trickster archetypes, for their job is to puncture the excesses of the principal hero. Cranky McCoy frequently does this to Kirk and to Spock. When Kirk pushes for some outrageous solution, McCoy puts the brakes on. “Damn it, Jim! I’m a doctor, not a bricklayer!” He also relights the fire when Spock dampens things too much with logic. I read one critic who commented that McCoy was a bigot. One assumes the comment was inspired by McCoy’s comments about Spock as a “pointy eared hobgoblin.” But I think it is an error to call McCoy a bigot: he has no such reaction to other Vulcans or other aliens. This reaction is specific to Spock. It is another manifestation of his function as a Trickster, to puncture the excesses of Spock’s logic.

Let’s start with McCoy. In this particular trinity of characters, he is firmly in the position of sidekick. Sidekicks are often Trickster archetypes, for their job is to puncture the excesses of the principal hero. Cranky McCoy frequently does this to Kirk and to Spock. When Kirk pushes for some outrageous solution, McCoy puts the brakes on. “Damn it, Jim! I’m a doctor, not a bricklayer!” He also relights the fire when Spock dampens things too much with logic. I read one critic who commented that McCoy was a bigot. One assumes the comment was inspired by McCoy’s comments about Spock as a “pointy eared hobgoblin.” But I think it is an error to call McCoy a bigot: he has no such reaction to other Vulcans or other aliens. This reaction is specific to Spock. It is another manifestation of his function as a Trickster, to puncture the excesses of Spock’s logic.

As a doctor, of course, McCoy is also a Transformer, changing the things around himself. But this is often secondary to his function as a Trickster. In the film, when McCoy first arrives on the scene, he transforms Kirk’s situation from being solitary to having a friend.

As a doctor, of course, McCoy is also a Transformer, changing the things around himself. But this is often secondary to his function as a Trickster. In the film, when McCoy first arrives on the scene, he transforms Kirk’s situation from being solitary to having a friend.

Spock is in many ways Kirk’s Shadow. In being such, he also highlights the point I make in The Scribbler’s Guide to the Land of Myth that a Shadow is not necessarily an evil figure. In this case, where Kirk is often passionate disorder, Spock is the opposite of that, emotionless (apparently) order. But Spock is also a Threshold guardian: he oversees the possibilities of Kirk’s choices. In the film, he is the one who has constructed the Kobayashi Maru test which winnows out candidates for command. Kirk, of course, thwarts this judgement, so Spock plays the next checking move of questioning Kirk’s ethics. By doing so, he forces Kirk to become more than just contrary, to find the justification for his actions.

However, the one thing Spock is not, or rather is not best at, is being a Ruler. He treats his judgements as absolute, and so does not readily attend to the advice of his subordinates, at least not when he is in command. In the film, when Kirk (fulfilling his function as First Officer in putting forward his criticism of Spock’s choice and offering an alternate) counters him, Spock over-reacts. He uses his authority not simply to remove Kirk from the bridge, but to abandon his appointed First Officer on the inhospitable and nearly deserted planet. This is not wise leadership one would expect from a Ruler.

Kirk, however, is a Ruler. Although he frequently pushes the envelope of a circumstances (a manifestation of his being a Transformer and Trickster), he does pay attention to the skills of his subordinates. He delegates tasks appropriately.

Kirk, however, is a Ruler. Although he frequently pushes the envelope of a circumstances (a manifestation of his being a Transformer and Trickster), he does pay attention to the skills of his subordinates. He delegates tasks appropriately.

This trio of characters provide balance and challenge to each other. The dynamic between them continually shifts about; it is never static. This is why they continue to be a fascinating set of characters.

(Pictures are property of Paramount Pictures.)

I agree with your analysis. Of the classic three, McCoy was the one I most identified with. Trickster figures repulse me, so I never liked Kirk. I did like and sort of identify with Spock, but McCoy was just so human that I thought he was fabulous.

Trickster figures are frequently unsettling, so I quite understand why you’d be repulsed by them. Does that include Bugs Bunny? 😉

I’m repulsed-attracted by Tricksters, I am attracted by their cleverness, but repulsed by their deciet. I don’t like hidden agendas. Or rather, I’m content with people who have open-and-transparent deep agendas (e.g. get X into power, stop Y becoming law, ensure Z happens), and do things which they say or imply are for one reason, but really serve the deep agenda. Which is why, I guess, I like Kirk, but not Bugs Bunny.

Back when I was in early phases of studying mythology and archetypes, I too was repulsed by Tricksters. In spite of the fact that one of my favorite literary figures was Odysseus. Somehow the two did not connect in my mind: the type in action and the type as described objectively. It was a long time before I realized why Trickster figures are so often Culture Heroes. The persistence to “do the whatever” in the face of all opposition usually requires the ability to divert the attention of the Bigger Power — to trick them.

But such characters can be annoying, because… well, they do carry a bit of chaos with them.

Which may be why I never quite found the dichotomy of Order versus Chaos in Michael Moorcock’s Elric stories and Zelazny’s Amber books to be quite as emotionally compelling. I realize they did not want to get into the “religious” territory of posing Good versus Evil, so they opted for the next strongest dichotomy, which is indeed Order versus Chaos. The problem is that chaos in and of itself is not necessarily evil — and as the past decades of study in chaos theory have show, even chaos has its own degree of order and structure.

No love for Bugs, eh? 😀 Well, he’s not to everyone’s taste.