(Originally posted on LiveJournal)

Now, mind you, I like a lot of William Goldman’s work. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Princess Bride. He’s a terrific writer.

But he is also responsible for the single most problematic quotation associated with Hollywood in existence. I firmly believe that it has become an excuse for storytellers in Hollywood to turn off their brains, to ignore story logic, to indulge their personal whims whether or not it makes sense. Really. I blame this quote.

“In Hollywood, nobody knows anything.” — William Goldman.

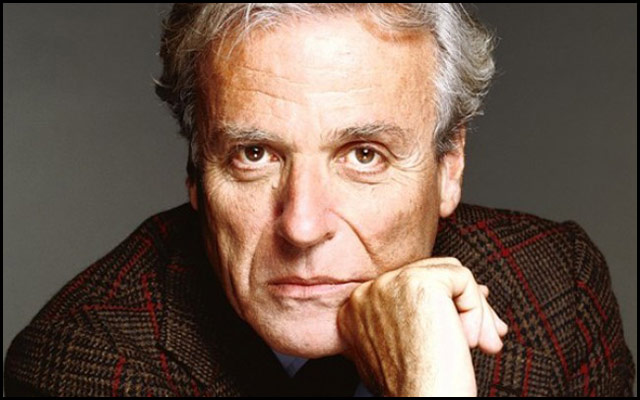

William Goldman

There you have it. When writers can’t figure their way out of a story problem, or even don’t want to do the work to figure it out, when writers don’t want to give up a favorite sequence in their script that they feel sure will knock the socks off everyone, in spite of their first readers telling them “no”, when writers feel that something is wrong, but don’t know what — that quotation gets trotted out, as if it excuses them from dealing with the problem. “Oh well, as William Goldman says, nobody knows anything anyway.”

Now, admittedly, there are plenty of examples of some brainless decisions being made by Powers That Be in Hollywood. Such as the head of Warner Brothers deciding that because their last few films with female leads have tanked, women therefore cannot carry a movie, ever, and therefore Warners will not greenlight a film with a female principal lead.

The fact that the stories for those films were bad, no, that can’t have anything to do with it. It’s all the women’s fault. We’ll completely overlook those films that were indeed carried most successfully by women: such as Silence of the Lambs, The Sound of Music, Mary Poppins, The Queen. Not a successful film in that bunch, is there? Not big box office, or Academy Awards?

The problem is that most people don’t want to take the time to figure out why something “doesn’t work”. Nor do they distinguish different types of “doesn’t work”.

I once tried pitching a script idea to the Disney Studio where Maid Marion was the main character. I called it Marion of the Woods. When I submitted the idea, the response I got back from the representative of the story department at the studio was that Robin Hood was a flop for movies now. He pointed out that Disney had done a Robin Hood film years before — the animated flick, where animals took the parts of the tale. I was pitching a live action. He then went on to observe that not even Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn could make a hit of Robin and Marion. Therefore, Robin Hood was dead as a film property.

I was a bit flabbergasted at the reasoning. Robin and Marion is a beautifully made and acted film. It’s actually one of my favorites. But I know full well why it did not do well at the box office: in general, audiences do not want to watch stories of the death of heroes, especially the “he’s going to die soon, anyway, because he’s old” type, especially of the legendary type of hero that Robin Hood is. Legendary heroes are supposed to go on forever, or their ends are supposed to be obscured from everyone. That is, if you aren’t going to give them the big victory and sacrifice type of ending that William Wallace gets in Braveheart. But the deaths in Robin and Marion are not comfortable: Marion’s declaration at the end of the film as they are dying makes us uneasy — “I loved you more than God.”

I was a bit flabbergasted at the reasoning. Robin and Marion is a beautifully made and acted film. It’s actually one of my favorites. But I know full well why it did not do well at the box office: in general, audiences do not want to watch stories of the death of heroes, especially the “he’s going to die soon, anyway, because he’s old” type, especially of the legendary type of hero that Robin Hood is. Legendary heroes are supposed to go on forever, or their ends are supposed to be obscured from everyone. That is, if you aren’t going to give them the big victory and sacrifice type of ending that William Wallace gets in Braveheart. But the deaths in Robin and Marion are not comfortable: Marion’s declaration at the end of the film as they are dying makes us uneasy — “I loved you more than God.”

Anyway, instead of asking the audience what the problems were with something that flops, the Powers That Be make arbitrary decisions about what they consider to be the factors. Actress X is grossly overpaid because her last couple of films flopped. It must be her fault that they flopped. It couldn’t possibly be that the script was flawed, or the director clumsy. Because really, “nobody knows anything.”

I admit, I could make a serious crusade out of this. After all, I’m about to launch a book on mythic motifs for writers, and I’m claiming that I actually do know something.

Comments

dannydonovan – Sep. 23rd, 2008

And I always thought the biggest problem with story telling in Hollywood is the audience is too dumb to appreciate good things. Hence why Larry the Cable Guy keeps getting cast in things, and Serenity barely made enough to keep Joss Whedon from jumping out a window.

I think the best version of the quote should be “the audience knows nothing.” :p

scribblerworks – Sep. 24th, 2008

“The audience knows nothing.”

Now that’s a distinct possibility. 😉

kalimac – Sep. 23rd, 2008

Well, you’re the expert here and I am not, but I’ll still say that it’s my observation that filmmakers don’t justify their conclusions on the basis that nobody knows anything. Instead, they justify them on the exact opposite: that they are sure that they know best.

Peter Jackson and Philippa Boyens, for instance (you knew I would mention them, didn’t you?), and even more their supporters like Kristin Thompson, base their changes to LOTR on an unexplicit but palpable absolute certainty of what does and does not work in films, of what is inherently appealing and what will generate good box office and what will not.

And they justify their decisions by pointing to a supposed nature of film, even though most of the specific examples they give would be equally applicable to a book, if they were valid at all. Rarely is there any consideration given to how the nature of film differs from the nature of books.

This is relevant because the one thing they did know about LOTR is that the book was successful the way Tolkien wrote it, and so filmmakers should proceed very cautiously before assuming they know more about storytelling than Tolkien did. Even after the fact, did specific changes actually help the film? Many viewers thought not. Did the film’s success come because, or despite, these changes?

I think there are good arguments that the changes hurt the films, both artistically and financially, but we can’t be certain. Nobody knows. Nobody knows anything. Only Jackson and boosters think they know, but they’re blowing hot air.

scribblerworks – Sept. 24th, 2008

The reality of the difference between prose and film is the dictum “show, not tell” — thus finding ways to dramatically show what the prose text tells. But that still doesn’t excuse Jackson et al.

As far as I’m concerned the worst they did was in the Aragorn and Arwen relationship. What? Aragorn gives up Arwen? She gives up and agrees to go to the West? And worse yet, somehow her life is tied to the existence of the Ring — even though NO logic is EVER given for that change!

All they needed for the stakes in the Aragorn and Arwen relationship is one Tolkien had already created: Elrond telling Aragorn that no man less than the King of Gondor shall have Arwen as wife.

I think the films’ successes came despite the bad changes – because they did do a good job visualizing the world, and the cast was well chosen.

But the point is, I do think that things about films “can be known”. If you’re willing to take the time, do the analysis, and are honest.

kalimac – Sep. 24th, 2008

The reality of the difference between prose and film is the dictum “show, not tell”

Perfect example of a claimed difference that in fact is no difference at all. Because there is no rule that’s beaten into the heads of prose fiction writers more than “show, don’t tell.”

The Aragorn and Arwen relationship is just one, and not even the worst, of numerous cases where Jackson mauled the dynamics of the story for reasons that make no sense at all, whether in film terms or prose terms or any terms whatever.

Sure, things about films can be known. But most of those things are things that are known because they’re just as true of any other kind of storytelling.

A few things are unique to film. A film story is much shorter than a novel, so a novel converted to film has to be condensed. Fair enough, and nobody is objecting to that necessity, though lots of Jackson-defenders are pretending that that’s the complaint. (They like to pretend it, because it’s easily dismissed.)

But others I’m not so sure of. Tolkien told a large part of his story in separate threads with virtually no intercutting. Conventional wisdom is that film isn’t amenable to that. OK, but when I saw the film Memento I realized that film can successfully do all kinds of tricks with time that I would never have thought were possible. So who knows if even that rule about intercutting simultaneous stories is true?

saje3d – Sep. 24th, 2008

Who knows WHAT they’re thinking? Not me.

In these days of reality TV, tasteless sitcoms, and “comedies” that are about as funny as a root canal, I can’t say that I find such a stupid decision on the part of Warner Brothers to be much of a surprise. There have been a LOT of movies with female leads I’ve enjoyed immensely, but, then again, I may not be a good gauge of what sells in America. I like movies and shows with some thought behind them, even if they’re only action flicks. And I loathe stupid comedies–that is, comedies featuring stupid people as a basis for the whole concept. The Ballad of Ricky Bobby? WTF? And I remember when spoofs had a creative spark of their own. Compare Airplane to Scary Movie. Or, for that matter, compare Ghostbusters or Beetlejuice to something like Blades of Glory. Hell, Bill and Ted were funnier than most of the stuff that they’re churning out these days, and those movies were hardly an example of high intellect in action.

Someone else mentioned Serenity and I have to agree. Fox pissed all over a great series like Firefly and turns out utter crap year after year after year and the people seem to gobble it up like it’s filet minon. Maybe Idiocracy wasn’t so far-fetched after all.

And it’s not like I’m some kind of entertainment snob. I LIKE a lot of the dramas out there, ranging from Bones to Criminal Minds to HBO’s newest offering True Blood. Some TV shows, at least, seem to mix comedy and drama fairly well. But too many actual movies take themselves a little too seriously, and what passes for straight comedy is, for the most part, simply wretched.

I wonder if Goldman’s quote might have been more accurate had it been “In Hollywood, nobody WANTS to know anything.”

Or, perhaps more accurately, nobody wants to take any kind of a risk. They’d rather rehash old ideas and plots and keep feeding successful franchises until people are sick unto death of them. I mean, seriously. Speed Racer as a live action movie? What the hell for? And a new Knight Rider? Hell, why not bring back the A-Team? Makes about as much sense. Gawd forbid anyone should have an original idea in Hollywood. Maybe that’s the real problem, not any alleged inability of female leads to carry a movie.

As bad as a lot of ’80s TV was, at least they were willing to take a few risks now and then. These days–not so much.

Telling a good story doesn’t take a genius. But it does take an actual interest in the story itself. Give the people characters they can relate to and the possibilities are limitless. But focus more on gimmicks and old, tired plotlines and it doesn’t matter WHO’S playing the lead.

Not that they’d ever listen to us

scribblerworks – Sep. 24th, 2008

Re: Who knows WHAT they’re thinking? Not me.

Well, hopefully they’ll eventually do a little listening to me. 🙂

kalimac – Sep. 24th, 2008

Re: Who knows WHAT they’re thinking? Not me.

Goldman in expanding on his dictum described the film industry as operating on a kind of cargo-cult principle (my comparison, not his) of what works. If a film with particular surface characteristics was successful, there’s a rush to make other films with the same surface characteristics. Thus, most obviously, the rush for sequels. Never any thought as to whether that’s actually what caused it to work or not.

scribblerworks – Sep. 24th, 2008

I think that’s one of the consequences of Goldman’s dictum being taken seriously.

Never any thought as to whether that’s actually what caused it to work or not.

Because “nobody knowns anything” — so let’s just copy the obvious form of the Last Successful Thing.

I suspect I have an uphill battle ahead of me in trying to change, even in a small way, that mentality.

Me and the Hard Way … longtime friends. 🙂

kalimac – Sep. 26th, 2008

Again, that’s certainly not the impression I get from descriptions I read of film producers. When they see a hit, rather than shrugging their shoulders and saying, “Well, let’s try one of those, who knows, it might work,” they act as if they’ve discovered the secret formula for sure-fire success. They’d hardly be willing to commit vast budgets if they were taking the former attitude.