A few years ago, I was in a burger joint with my screenwriting group. We’d had a good morning session giving notes and were unwinding over lunch. At the next table over, there were two guys talking. They were obviously screenwriters (the script bound with brads in front of one of them was one clue), one a newbie, the other a bit more practiced. Given the proximity in the restaurant, it was impossible not to overhear part of their conversation as we waited for our orders to arrive.

The “Practiced” Writer (I’m not sure just how much experience he had under his belt, but it was more than his companion had) was giving the Newbie some advice on how to beef up his script. Mr. Practiced was talking about mythic content in story. I’m not sure what the nature of Newbie’s actual script was, but Mr. Practiced was talking about using the story structure of a mythic story as the template for his own.

My friend J and I (we were sitting face to face) exchanged a glance with muted smiles. She knew I’d spent four years writing a book on mythic motifs in storytelling. (This was after I’d finished the book, but before it had seen print.) We both knew Mr. Practiced’s explanation was a little simplistic and off the mark.

But the Mr. Practiced upped the stakes on us by using Beowulf as an example of a mythic story.

I had to stop listening in, because it was hard not to burst out laughing. Not because I think Beowulf does not have mythic paterns in it. No, it was because I’d done my Masters thesis on Beowulf. If there was one heroic story I knew really well, it was that one. And Mr. Practiced was getting some plot elements of the heroic story wrong – missing their points.

J and I chuckled and gave our attentions back to our friends.

J and I chuckled and gave our attentions back to our friends.

But that occasion has stuck with me, because it points out the problem many people have in trying to understand how mythic patterns work in their own modern stories.

Part of the problem lies in how people regard the term “myth.” Many people think of specific stories when they hear the word “myth.” Like Mr. Practiced, they will cite a particular tale — Beowulf or The Odyssey or the quest for the Golden Fleece.

Filmmakers easily get caught in that place, with the result that we are given works like Clash of the Titans.

It’s the story of Perseus with other things thrown in. And of course the great title overlooks the fact that the mythic Olympian gods are not actually “the Titans” (which were a different generation of divine figures).

Now, it’s a fun action/adventure, so we can look at it as a fantasy and enjoy it as that.

Another approach would be to treat the mythic story as “just a story” in an ancient historical period. This approach would bring us Troy.

That film treated The Iliad as a historical tale and down-played the mythic and supernatural elements.

That film treated The Iliad as a historical tale and down-played the mythic and supernatural elements.

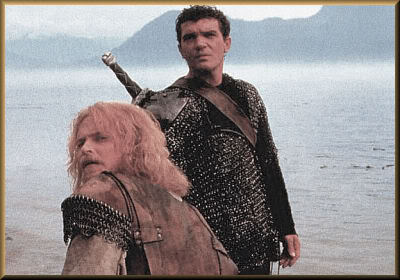

Much the same approach was given to Beowulf in The 13th Warrior.

Much the same approach was given to Beowulf in The 13th Warrior.

Gritty and realistic, but no fun when you get to the dragon part of the story. For that, you need to look at the version of Beowulf co-written by Neil Gaiman.

Gritty and realistic, but no fun when you get to the dragon part of the story. For that, you need to look at the version of Beowulf co-written by Neil Gaiman.

Of course, I have some disagreements with that version, particularly making the hero to be a liar (which is utterly contrary to my interpretation in my thesis). But it remains a version that pulls the story elements together fairly well.

Of course, I have some disagreements with that version, particularly making the hero to be a liar (which is utterly contrary to my interpretation in my thesis). But it remains a version that pulls the story elements together fairly well.

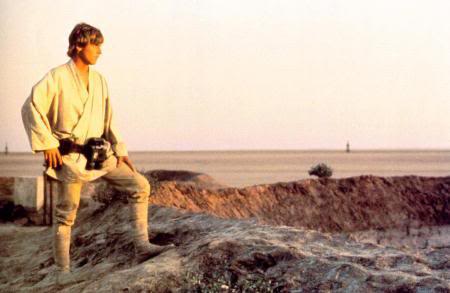

But all these examples don’t help the writer who has a “modern” story, but wants to figure out how to get that mythic magic into his story. He hears comments about how mythic the Luke trilogy of Star Wars is, and how George Lucas referenced The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

This gets the struggling writer wrestling with his story, trying to figure out what events in his story fit which steps of Campbell’s (or Chris Vogler’s) Hero’s Journey. He shifts events, squishes things into the cracks, makes up beats he thinks he needs, until the story has morphed into something alien.

This gets the struggling writer wrestling with his story, trying to figure out what events in his story fit which steps of Campbell’s (or Chris Vogler’s) Hero’s Journey. He shifts events, squishes things into the cracks, makes up beats he thinks he needs, until the story has morphed into something alien.

This is a point I make over and over in The Scribbler’s Guide: mythic motifs are flexible. They are also bare bones, not steel molds. The power of mythic motifs lies in their meanings, not in the specific story forms they take.

I’ll round out these musings by pointing to a movie that I suspect few people would quickly think of as “mythic”: Die Hard.

Modern. Action-adventure. Tough guy stopping terrorists. What’s mythic here?

Modern. Action-adventure. Tough guy stopping terrorists. What’s mythic here?

What is mythic is the primal drive for John McClane. All he wants is to get back to his wife. Hans and his gang throw extraordinary obstacles in John’s way. But all John wants is to get to Holly.

But guess what? That’s the heart of The Odyssey. It’s primal. It’s “mythic.”

But guess what? That’s the heart of The Odyssey. It’s primal. It’s “mythic.”

The pictures are property of their owners and are used here under Fair Use, for commentary only.